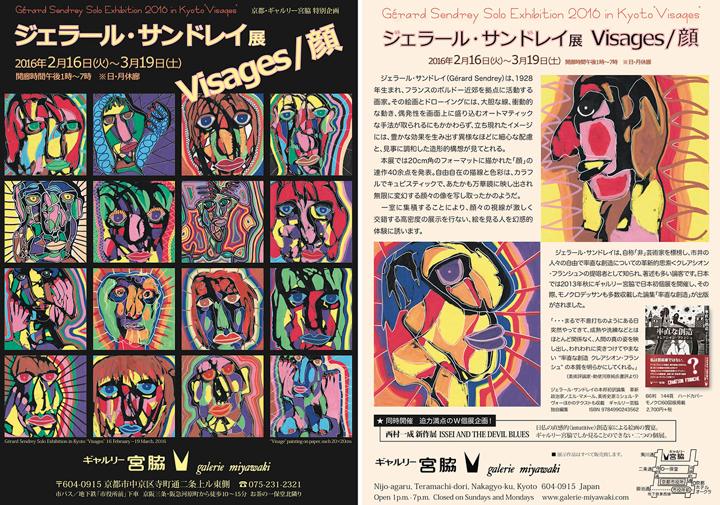

Gérard Sendrey "Visages"

16 February to 19 March, 2016The French self-taught artist Gérard Sendrey was born in 1928 in southwestern France. At university, he studied law and later he worked for many years as a civil servant in Bègles, a city near Bordeaux. Sendrey was almost forty years old when, in 1967, he began making art. At first he produced paintings but later he started to make drawings on paper, too.

In his drawings, Sendrey often uses a clear, simple line or silhouetted shapes to depict plants, human figures and other subjects. He also developed a technique in which he uses ink-covered objects, which he bounces or rolls over the surfaces of blanks sheets of paper to create abstract images. Sometimes he embellishes certain forms within those images to create recognizable subjects, such as faces or plants. In his paintings, Sendrey often uses bold outlines to distinguish the forms of houses, human figures or other subjects.

Sendrey’s works were first shown publicly in an exhibition at the Galerie du Fleuve in Paris in 1979. That exhibition attracted the attention of the Collection de l’Art Brut, a museum in Lausanne, Switzerland, which later acquired some of his works for its “neuve invention” collection. The French modern artist Jean Dubuffet, who created the term “art brut” (which means “raw art”) to refer to art made by self-taught artists on the margins of mainstream culture and society, primarily for themselves, also coined the term “neuve invention” (“new invention”) to refer to works of art that did not exactly fit into the art brut category but that shared certain aesthetic similarities with art brut.

Sendrey retired from his government job in 1988. The next year, he helped establish the Site de la Création Franche, a cultural organization in Bègles, which later became a museum. To contrast with the label “art brut,” which Sendrey considered too closely linked to Dubuffet’s theories, he created the new term “création franche.” This term may be translated as “free creation,” using an old sense of the French word “franche,” which means “free” or “emancipated.” (In 2013, Galerie Miyawaki published a book about Sendrey’s art with essays written by the artist himself, Noël Mamère, Michel Thévoz and Pascal Rigeade.)

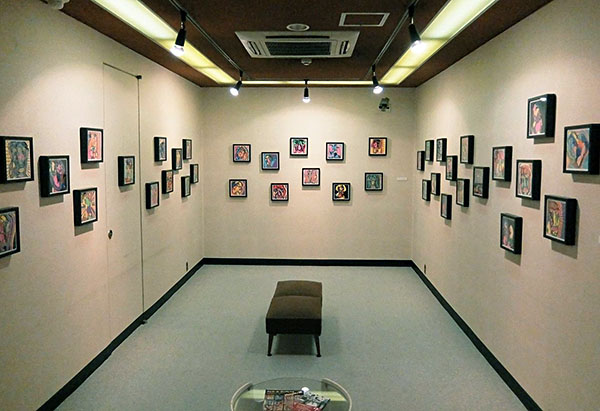

In the pictures Sendrey presents in his most recent exhibition at Galerie Miyawaki, the artist uses a bright palette, free-flowing lines and a consistent, 20-centimter-square format to create images that recall the spirit of both pop art and psychedelic art of the 1960s and 1970s. The character of these images is bold and full of energy. In them, faces sometimes appear disjointed in a cubist manner, with multiple eyeballs and lips appearing in a single composition. Sometimes hands or feet push their way into the pictorial space. In these works, Sendrey appears to have captured the energy of animated films or dynamic computer graphics in the format and context of more static, two-dimensional pictures.

With their powerful gazes, the subjects of these portraits seem to implore viewers to break through the invisible barrier that separates them from the world inside the pictures, to enter that world and to get to know these mysterious people with their brightly colored faces and peculiar gestures.

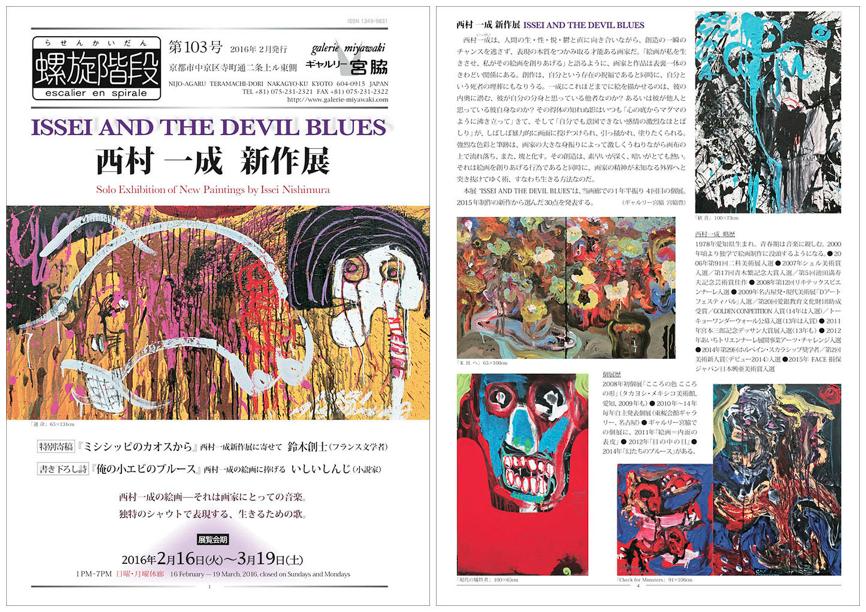

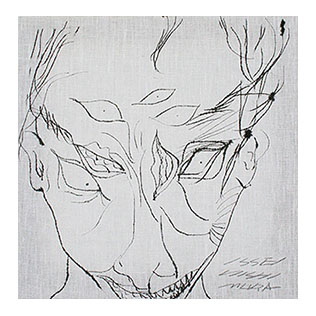

Issei Nishimura "Issei and the Devil Blues"

16 February to 19 March, 2016

16 February to 19 March, 2016The self-taught artist Issei Nishimura was born in 1978 in Aichi Prefecture, in south-central Japan. As a child, he displayed an aptitude for art-making and later, without receiving special training, he continued making drawings and paintings that reflected his abiding creative impulse. In Japan, Nishimura’s work has been shown in numerous exhibitions and has been recognized by various awards. In Kyoto, Galerie Miyawaki first presented the artist’s work in 2011 in an exhibition titled “Issei Nishimura Paintings: The Outer Surface of My Inner Self.”

In Japan, Nishimura’s art-making has been described as “uninhibited” and as conveying the artist’s “own desire,” which is sincere and seemingly unstoppable, to express himself in a visible, tangible way. Unfortunately, some observers have tended to romanticize Nishimura’s work in a manner that has been more distracting than illuminating. However, its feeling of immediacy and directness is its own allure.

With their bright, electric colors and unusual representations of plants or human forms, the images Nishimura produces are not easy to classify. In one picture, a man has a potato in place of a head. In another, a face is covered with eyeballs, and in a third the colors of a slice of cake drip off the canvas like the strange material of an otherworldly, self-destructing object.

-->> See Digital Catalog of the 50 selected paintings 2013-2014 by Issei Nishimura

Art like Nishimura’s comes from the still-unknown core somewhere in the human psyche where creativity resides. Insofar as it appears to reflect its maker’s pure, raw emotional-psychological energy and creative impulse, it is expressionistic art. Nishimura does not filter what he makes through any theoretical structures. Normally his mostly abstract images appear to be devoid of any overt, strictly limiting cultural references. Nishimura’s art somehow feels deeply personal. As a result, like much of the most appealing, intriguing abstract art, whatever he might intend for his images to mean ⎯ or maybe they have no intended meanings at all ⎯ they invite viewers to bring to them and read into them their own values, references, fantasies or interpretations.

|

In the works on view in Nishimura’s latest exhibition, “Issei and the Devil Blues,” ghoulish or half-formed faces emerge in some compositions, while others are completely abstract, made up of flurries of thick brushstrokes set against flatter, solid backgrounds or passages in which brushwork, linework and washes of transparent color collide. In one diptych painting, thickets of broad brushstrokes give shape to bunches of flowers emerging from some very malleable vases.  In one panel of a triptych, a band of white fabric extends outward from the picture plane, surrounding a haunting green face that is set against a light-blue ground. Nishimura’s works, in which drawing plays a prominent role, are especially interesting. In the current exhibition, one work features an attentive cat rendered with a few fine, expertly placed lines. Another, with echoes of Jean Cocteau’s drawings of fantasy subjects, shows a close-up of a face with several mouths and eyes.

In one panel of a triptych, a band of white fabric extends outward from the picture plane, surrounding a haunting green face that is set against a light-blue ground. Nishimura’s works, in which drawing plays a prominent role, are especially interesting. In the current exhibition, one work features an attentive cat rendered with a few fine, expertly placed lines. Another, with echoes of Jean Cocteau’s drawings of fantasy subjects, shows a close-up of a face with several mouths and eyes.

In Nishimura’s work, some Western viewers may find affinities with the so-called neo-expressionistic art that was popular in the art markets of the United States and Western Europe during the 1980s, but that art-making style was more of a passing trend. By contrast, like the most authentic self-taught artists, Nishimura makes his art not in response to any momentary style trends or to please a particular audience but rather for himself. That urgent impulse ⎯ or unsinkable need ⎯ to create is the real subject of Nishimura’s art ⎯ not any notion of chaos or any other romanticized interpretation of the images he produces or the romanticized analysis of the source of his creativity.

Naoki Nishiwaki "Obsession and Humour"

1 April to 24 April, 2016

1 April to 24 April, 2016Naoki Nishiwaki was born and grew up in Osaka, where he lives and works today. He began making drawings when he was about four years old. After finishing high school, Nishiwaki enrolled at an art school in Shiga Prefecture to study sculpture, but his interest in picture-making remained strong. By the time he graduated from art college, he had shifted his major field of study from sculpture to information design (a field that is often known as “communication design” in American and European schools).

Nishiwaki continued his studies at the graduate level at the Institute of Advanced Media Arts and Sciences in Gifu Prefecture in the broader field of “media creation.” After earning his master’s degree, Nishiwaki worked as an assistant researcher at the school for one year. Later, during the summer of 2008, he fell ill and was hospitalized for several months.

After being discharged from the hospital, he went regularly to a day-care clinic, in whose waiting room, working at a big table, he was able to make large-format drawings on paper. This day-care center offered no structured art-therapy program. Instead, Nishiwaki brought his own art-making supplies with him and simply took advantage of the availability of a large table, which he used as a workspace, ignoring the would-be distractions of the clinic’s employees or visitors passing back and forth through the waiting room. He worked in these conditions for three-and-a-half years. Today he makes his drawings both in a rented studio space and at his home.

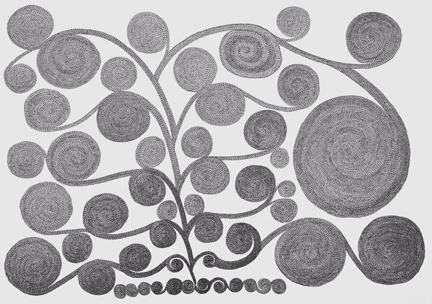

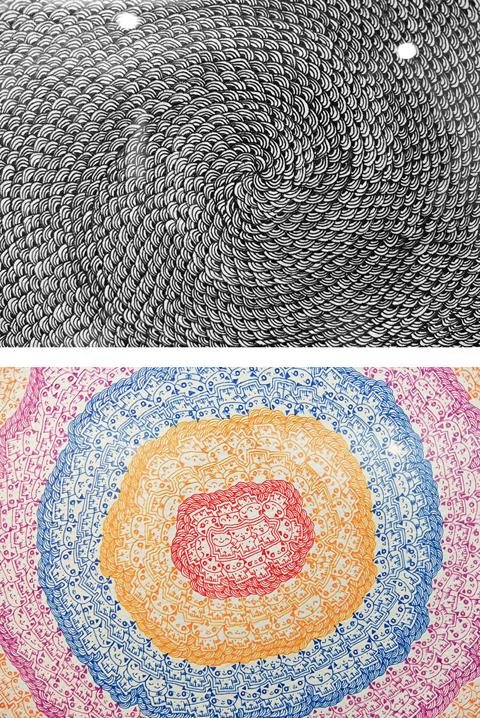

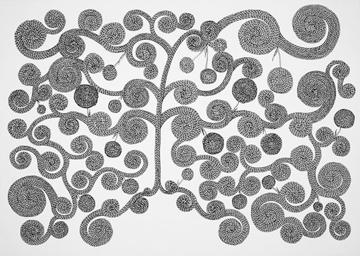

To create his pictures, Nishiwaki uses ballpoint pens on paper. In one of his common techniques, the artist draws what appear to be endless lengths of braided string, which form circular flower forms emerging from long, serpentine stems. Most of these images are monochromatic. Nishiwaki also creates monochromatic or multicolored compositions made up of concentric circular forms whose tiny component parts are countless, simple line drawings of the faces or the faces and bodies of a cute-cat figure that has become one of his signature motifs. Sometimes his pictures combine both his braid-like motifs and his tiny cats in abundance. At first glance, from a distance, his images tend to read visually as randomly patterned geometric abstractions, but upon close inspection, they reveal that they are largely made up of neatly ordered agglomerations of his braid motifs or kitty-cat faces.

This obsessive use of repeated motifs to build up pictorial form, construct compositions and fill a two-dimensional image’s pictorial space finds echoes in and affinities with the work of other artists within the histories and contexts of both modern art and the related fields of art brut and outsider art. The Japanese modern artist Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Net paintings of the 1950s and 1960s come to mind, for example, as do the drawings of the Belgian self-taught artist Joseph Lambert (born 1950), who uses only irregular stripes of color to create abstractions that may be perceived as imaginary landscapes. The drawings of the contemporary Japanese self-taught artist Hiroyuki Doi (born 1946) also reflect an obsessive impulse. Doi uses only miniscule circles, drawn in vast quantities, to produce voluminous compositions in ink on paper.

In Japan, viewers of Nishiwaki’s works may recognize in their kitty-cat motif an expression of the widespread admiration of kawaiimono (“cute things”) that is such a pervasive part of Japanese popular culture. Non-Japanese viewers might find that motif to be too cute (and, therefore, sentimental and even distracting from the impact of the artist’s otherwise attractive abstract compositions) or they might just overlook it.

By contrast, many of the compositions Nishiwaki develops using his braid motif, whose forms resemble vine-like, flowering plants, feel more intriguing, because their fundamental component part is an abstract element to begin with. Some of these plant-like compositions resemble the symmetrical or nearly symmetrical tree of life that is such a prominent theme in the folk art of many parts of Europe and the Americas.

Among contemporary Japanese artists, Nishiwaki has developed a deeply personal and recognizable, signature style. As he moves forward, it will be interesting to watch and see if and how he may be able to further develop his art-making techniques and their expressive potential.

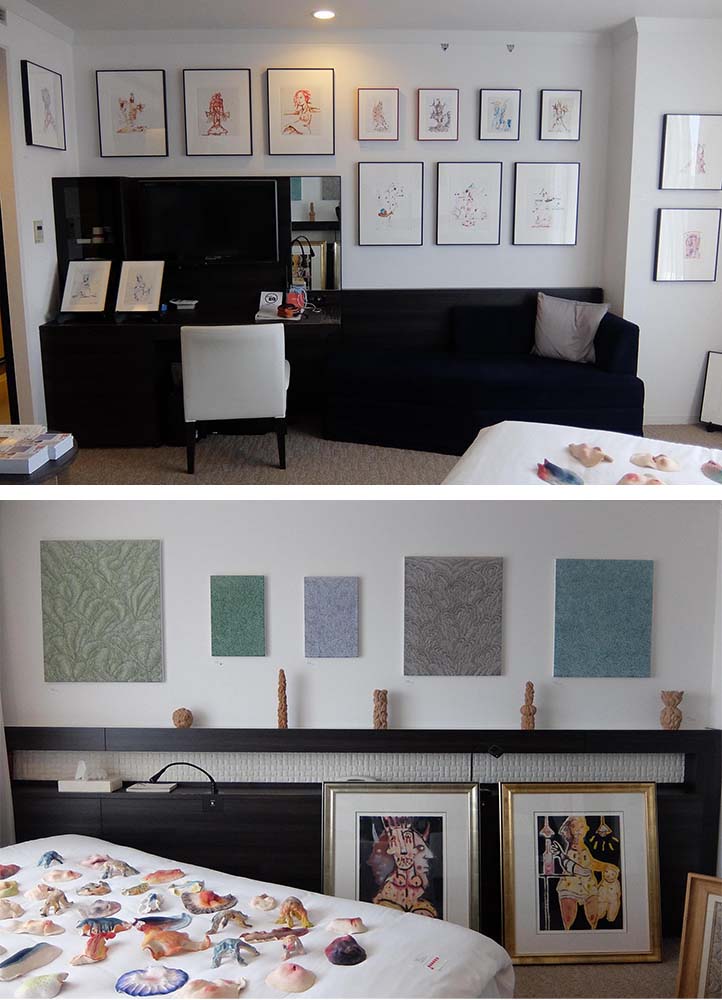

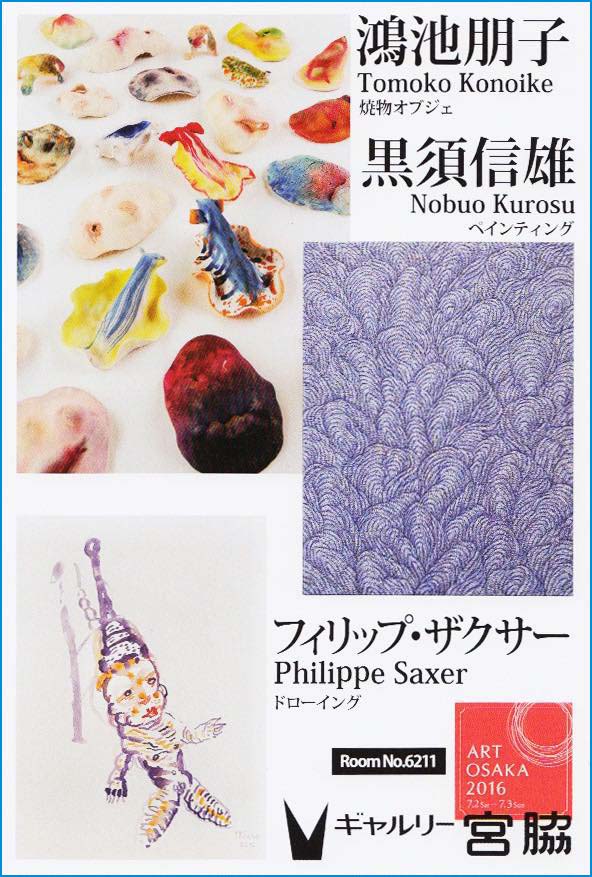

Tomoko Konoike, Nobuo Kurosu and Philippe Saxer

1, 2 and 3 July, 2016, Hotel Granvia Osaka, room #6211

1, 2 and 3 July, 2016, Hotel Granvia Osaka, room #6211In early July, Galerie Miyawaki participated in Art Osaka 2016, an art fair that took place at the Hotel Granvia Osaka.

There, the gallery featured the works of Tomoko Konoike and Nobuo Kurosu from Japan, and, from Switzerland, the late Philippe Saxer. Now, during the month of July, a selection of works by these same artists is on view in the ground-floor space at Galerie Miyawaki in Kyoto.

Tomoko Konoike was born in 1960 in Akita Prefecture, in northern Japan, and earned an undergraduate degree in Japanese traditional painting at Tokyo University of the Arts. She worked as a toy and furniture designer in the past, and in recent years has become known for a diverse body of work in various media whose themes allude to primordial, natural forces and whose poetic aspects hint at a fascination with mythical tales and the world of dreams.

Some of Konoike’s sculptures have included depictions of wolves with six legs and a mountain with a nose and mouth; often she covers the surfaces of such forms in a mosaic manner with fragments of broken mirrors. A few years ago, in one of her two-dimensional images, she portrayed a big bee (with human legs) in flight, its feet tucked into black sneakers.

Although Konoike has become known as the creator of numerous, large-scale sculptural or two-dimensional works, Galerie Miyawaki is showing a group of her smaller pieces made of unglazed clay. She has coated them with transparent washes of watercolor and has said that she likes the effect created by the paint that seeps into and colors her fragile material.

With their odd forms that bring to mind sea creatures, body parts (including human genitalia) or hardened pieces of some gigantic animal’s thick skin, they exude an air of mystery. Individually and together, these unusual objects are both hauntingly enticing and beautifully grotesque.

With their odd forms that bring to mind sea creatures, body parts (including human genitalia) or hardened pieces of some gigantic animal’s thick skin, they exude an air of mystery. Individually and together, these unusual objects are both hauntingly enticing and beautifully grotesque.

Nobuo Kurosu was born in 1962 in Tokyo and earned his undergraduate degree in oil painting from Tama Fine Arts University in the Japanese capital. He has had numerous solo gallery exhibitions there; this presentation of some of his acrylic-on-canvas paintings in Kyoto is in keeping with Galerie Miyawaki’s interest in a kind of contemporary abstract image-making in which artists employ well-developed methods of handling their materials that are as distinctive as the different formal languages they use to create their pictures. (See, for example, the works of Naoki Nishiwaki, which the gallery also shows.)

To date, neither in Japan nor anywhere else have any in-depth critical examinations of Kurosu’s work been published. However, the artist himself has written some brief texts that have appeared in print. In them, he has not really discussed his art-making methods. Instead, he has focused on the theme of light and darkness, in which he appears to have a very keen interest. In one of his texts, Kurosu observes, “Just as one can speak of the intensity of light, similarly, one should speak of the intensity of darkness, too.” He cites a legend from ancient Japanese mythology, in which deities bring light to Earth, and notes that “the roots of light lie in darkness.”

The artist’s preoccupation with light and dark takes the form of monochromatic compositions in which thick, fluffy ribbons of plant-like forms spread organically and unstoppably across his pictorial space. There is an unmistakably obsessive quality in what appears to be Kurosu’s desire, need or determination to cover each canvas’s surface with a dense, unfolding pattern that resembles some kind of runaway plant growth.

Does his subject matter spur him on to create, or is Kurosu in control of the images he creates? Looking at his pictures, some viewers might sense that they almost will themselves into existence.

The Swiss self-taught artist Philippe Saxer (1965-2013) was a naturally gifted, prolific maker of drawings, as well as of paintings and sculptures. Often he created his works on paper in just a few minutes, using ink and traditional, metal-nib pens. He began drawing as a child and was interested in comics but was not able to study cartooing when he was growing up. He did do an apprenticeship to learn glass-art techniques and later made works in which, as in stained glass, he used lead to assemble objects made of many pieces of glass. In the early 1980s, when he was still a teenager, the Vitromusée, a museum of glass art in Romont, Switzerland, acquired three of Saxer’s creations.

Saxer was a troubled soul who suffered from debilitating anxiety. For many years he resided at or received treatment from a university-affiliated psychiatric clinic near Bern, Switzerland. It was at this same institution (in its earlier form, as the Waldau Psychiatric Clinic) that the legendary Swiss art brut master Adolf Wölfi (1864-1930) also resided and produced his masterpiece in the early 20th century, a 45-volume, illustrated narrative about the creation of the universe by his own alter ego.

Saxer took his own life at the end of 2013 after having struggled with his anxieties for many years.

He left behind a large body of work, including thousands of drawings, in which faces, bodies, flowers, animals, fish, plant-like forms and all sorts of everyday objects appear, sometimes as the solitary subjects of relatively spare compositions and sometimes in abundant groupings. Saxer’s line always appears as fluid and confident as his images feel immediate and impulsive.

He left behind a large body of work, including thousands of drawings, in which faces, bodies, flowers, animals, fish, plant-like forms and all sorts of everyday objects appear, sometimes as the solitary subjects of relatively spare compositions and sometimes in abundant groupings. Saxer’s line always appears as fluid and confident as his images feel immediate and impulsive.

In the current exhibition, in some of the female faces or bodies that appear in drawings in red and white colored pencil on paper, Saxer exaggerates his subjects’ eyes, breasts or torsos in ways that bring to mind the psychosexually charged drawings of the Austrian expressionist artist Egon Schiele (1890-1918). They also share affinities with the drawings of the contemporary American artist David Scher and other modern and contemporary artists whose work is deeply rooted in daily, routine, unstoppable drawing (in such media as ink, pencil, colored pencil, watercolor or gouache).

In an article published in a Swiss online newspaper shortly after Saxer’s death, Otto Frick,

the retired head of the art workshop at the psychiatric clinic with which the artist had long been associated, recalled, “When he was feeling completely bad or completely good, he could not bring himself to paint, but the rest of the time, he could sit down and in one hour produce between twenty and forty picures.”

the retired head of the art workshop at the psychiatric clinic with which the artist had long been associated, recalled, “When he was feeling completely bad or completely good, he could not bring himself to paint, but the rest of the time, he could sit down and in one hour produce between twenty and forty picures.”

With this concentrated selection of works by Konoike, Kurosu and Saxer, Galerie Miyawaki continues its exploration of the work and ideas of contemporary artists who have tended not to follow mainstream art-making trends but who instead have pursued their own deeply personal visions. In doing so, they have created art forms whose often obsessive edge is a large part of their allure.

Toshiro Kuwabara (1953-2014) "The Remaining Works"

12 July to 30 July, 2016, Galerie Miyawaki, Kyoto, Japan

12 July to 30 July, 2016, Galerie Miyawaki, Kyoto, Japan

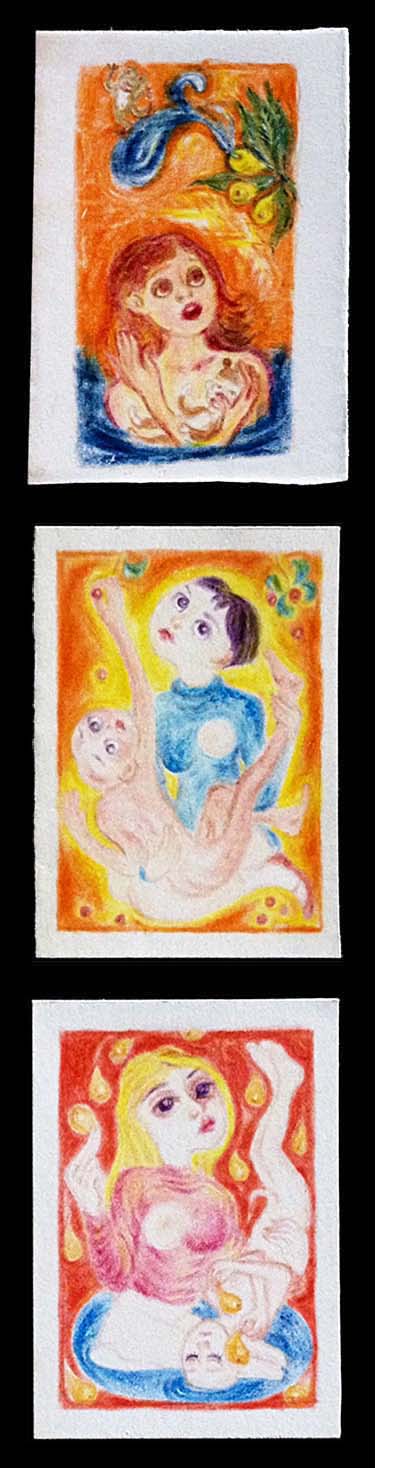

The drawings in colored pencil on paper of Toshiro Kuwabara (1953-2014) constitute one of the most interesting and unusual finds to date in the still-young, fast-evolving field of so-called Japanese art brut. It does not surprise me that a selection of these unusual drawings should be presented at Galerie Miyawaki in Kyoto, a gallery whose increasing involvement with the creations of inventive, original self-taught artists has led to some noteworthy discoveries and become an essential part of its programming.

Born in Ibaraki Prefecture, northeast of Tokyo, Kuwabara was a sickly child who suffered from asthma. When he was in his twenties, he became a shut-in, so much so that his family constructed a little hut for him on its property. It became his atelier. It was his private shelter and refuge, even though he continued to reside in the family house, in which he had his own room (although he did not speak with anyone). In his little hut, unbeknownst to his family, Kuwabara produced his drawings, the existence of which he only revealed to his younger brother Hiroaki when the older, self-taught artist was diagnosed with cancer at the age of sixty. By that time, Toshiro’s disease was so far advanced that it was not possible for him to undergo any curative treatment.

Hiroaki, an artist who was associated with fellow admirers of surrealist art, recognized the significance of his brother’s drawings and helped make them publicly known. Toshiro, who had made drawings since his early childhood and who, throughout his life, enjoyed reading, had been exposed during his high school years to basic modes of drawing, painting and printmaking, but the works he left behind after his death do not fit easily into any familiar category of Japanese art.

Hiroaki, an artist who was associated with fellow admirers of surrealist art, recognized the significance of his brother’s drawings and helped make them publicly known. Toshiro, who had made drawings since his early childhood and who, throughout his life, enjoyed reading, had been exposed during his high school years to basic modes of drawing, painting and printmaking, but the works he left behind after his death do not fit easily into any familiar category of Japanese art.

With their soft handling of a simple, bright, colored-pencil palette and their depictions of fresh-faced young women, at first glance his pictures bring to mind certain kinds of European folk art imagery. But closer examination of his drawings reveals that his maidens are often partly or fully naked, sometimes tied up and usually menaced by nearby male figures or animal-like gremlins.

The air of foreboding surrounding his subjects’ predicaments contrasts dramatically with Kuwabara’s gentle handling of his materials. The tension that emerges from this discrepancy gives his art a peculiar allure and evokes affinities with the works of such well-known, American self-taught artists as Henry Darger (1892-1973) and Morton Bartlett (1909-1922), in which a psychosexual charge can also be detected. (Darger made complex collage drawings to illustrate a story he had written, in which little girls with male sex organs fight battles against evil monsters. Bartlett made and photographed small-scale, life-like plaster dolls depicting young girls, sometimes in nude poses.)

The air of foreboding surrounding his subjects’ predicaments contrasts dramatically with Kuwabara’s gentle handling of his materials. The tension that emerges from this discrepancy gives his art a peculiar allure and evokes affinities with the works of such well-known, American self-taught artists as Henry Darger (1892-1973) and Morton Bartlett (1909-1922), in which a psychosexual charge can also be detected. (Darger made complex collage drawings to illustrate a story he had written, in which little girls with male sex organs fight battles against evil monsters. Bartlett made and photographed small-scale, life-like plaster dolls depicting young girls, sometimes in nude poses.)

The artist left behind just over one hundred drawings, of which Galerie Miyawaki’s presentation includes twenty-eight pieces. Made during the period from roughly 1980 to 2000, they represent some of the most potent examples of Kuwabara’s art, whose secrets he took with him when he died two years ago.

A Season of Discoveries Edward M. Gómez

Art galleries are commercial enterprises. They aim to sell merchandise, and the goods on offer are works of art. However, works of art are not like other, more common products, such as clothes, packaged foods or household items. They are born of each artist’s inexplicable spirit and of his or her deeply personal and often urgent need to create, to express something and, through the products of an irrepressible imagination, to send messages to the world.

The series of exhibitions Galerie Miyawaki has presented in recent months, about whose featured artists’ works I have commented in this current series of brief essays, has offered ample evidence of the diverse forms contemporary artistic expression can take and of the range of themes today’s imaginative artists are addressing.

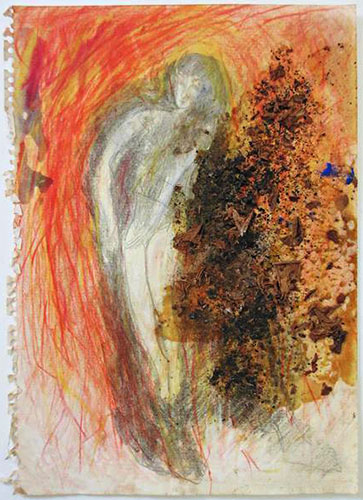

Reflecting the gallery’s interest in works of art that are both highly original in concept and physically well crafted, this recent series of exhibitions has featured paintings, drawings and works in other genres by schooled, partly trained or self-taught artists. In all of their works, the impulse to create may be felt in the clever or innovative handling of materials, from Naoki Nishiwaki’s development of a simple, formal vocabulary of spiraling lines that resemble braided ropes to n.t.’s experiments with texture-rich painting surfaces encrusted with bits of fabric and other media.

Simple but psychologically intense are the abstract forms or recognizable or semi-abstract human figures of Nobuo Kurosu, Tomoko Konoike, Issei Nishimura and Philippe Saxer. Gérard Sendrey makes images that revel in the expressive power of their line, while the psychosexual intensity of Toshiro Kuwabara’s gently toned, at first glance naïf-feeling images of young female nudes prompts unexpected double-takes.

Galerie Miyawaki’s recent exhibitions have demonstrated that a search for compelling works of art made by both Japanese and foreign artists, works that otherwise probably would not be shown in Japan, is one of the gallery’s main pursuits. Thanks to this ambitious research effort (and the catalog- and newsletter-publishing program that has complemented it), Galerie Miyawaki has become a noteworthy venue in Japan for unconventional works of art that cannot be easily classified according to the latest trends or that merely respond to the fashions of the style-chasing mainstream.

For art dealers and collectors alike, there may be challenges in getting to know art forms that are so uncommon and distinctive. At the same time, though, in different and resonant ways, the works featured in Galerie Miyawaki’s recent exhibitions have offered some memorable and unexpected rewards.

Edward M. Gómez

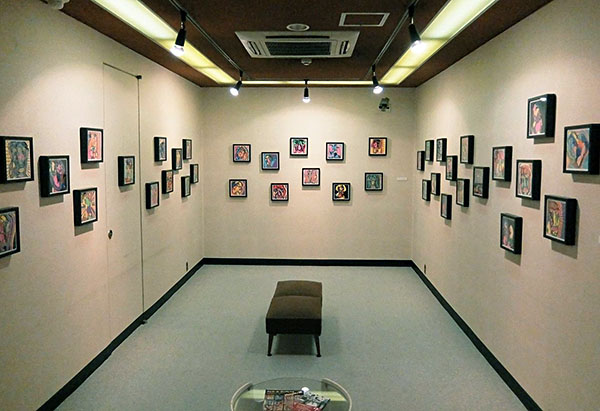

About Galerie Miyawaki in Kyoto, Japan

*****Located in Kyoto’s Teramachi-Nijo neighborhood, an area known for it’s fine art and antiques, Galerie Miyawaki is one of the greatest galleries in the Kansai region holding planned exhibitions as well as presenting its permanent collection. The gallery was originally established in 1958, eventually relocating to its present location in 1973; for forty years it has hosted a succession of unique exhibitions to become Kyoto’s representative dealer in modern art. *****The five-story gallery building was designed for optimal use as an exhibition space; one of its most distinctive characteristics is its spiral staircase that connects the building’s first through third floors. This allows visitors to experience the gallery by ascending and descending through its spaces vertically. *****While previously specializing in surrealist art and art informel, in recent years the gallery has become involved in even more eccentric activities by shifting its focus to include more marginal movements in modern art such as art brut, or outsider art. *****The sense of art appreciation here is based upon the idea that modern art should represent a continuity and symbiosis between the old (the known) and the new (the unknown), and the idea that a primal desire for life is the foundation for all creativity. *****Presenting a diverse lineup chosen without strict regard for the medium of the work or the fame of the artist, the gallery often hosts overseas artists’ premier exhibitions in Japan, consistently drawing the attention of both critics and collectors. |